by Larry Campbell | May 13, 2021 | Education |

George Will, as you likely know, is a conservative political commentator, mostly for the Washington Post. He is an excellent and articulate writer and usually provides food for thought, whether I agree with him politically or not. I also give him high marks for maintaining a strong sense of balanced sanity during the troubling times our nation has been through.

A recent (4/14/21) column of his had some interesting perspectives on technology, which I think can have pertinent connections in education. Allow me to lay some groundwork.

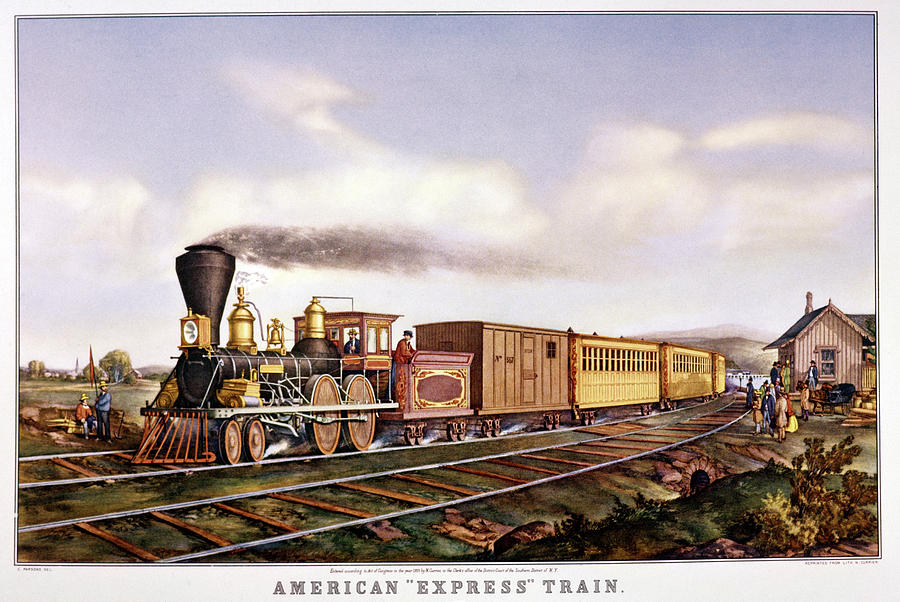

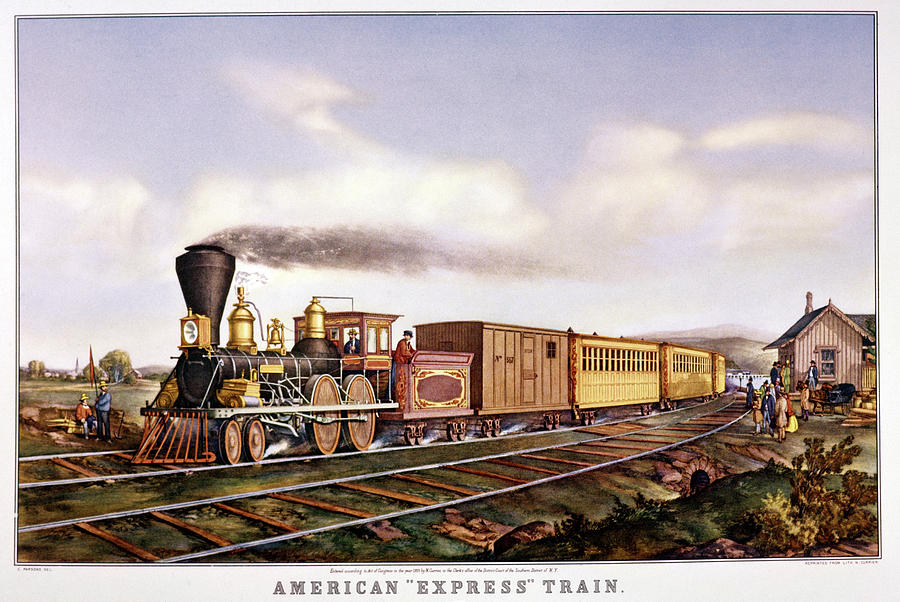

The column refers heavily/often to a book called “Lincoln on the Verge: Thirteen Days to Washington”, by Ted Widmer, a historian at City University of New York. The book is apparently a detailed record of president-elect Lincoln’s 1861 journey by train from Springfield, Ill to Washington, DC.

The column refers heavily/often to a book called “Lincoln on the Verge: Thirteen Days to Washington”, by Ted Widmer, a historian at City University of New York. The book is apparently a detailed record of president-elect Lincoln’s 1861 journey by train from Springfield, Ill to Washington, DC.

I’m regretfully omitting fascinating background here, but in a nutshell, Will concludes (with Widmer’s help) that the two 19th century technologies of the railroad and the telegraph were as socially and culturally transformative as the 20th century technologies of the internet and social media are today. And that the uneasiness about these changes was as great as the distress many feel about how our technologies are shaping society today. (In 1858, for example, the first transatlantic cable connected New York with London. The New York Times wondered if this might make the velocity of news “too fast for the truth”. Hmmm . . . )

I’m regretfully omitting fascinating background here, but in a nutshell, Will concludes (with Widmer’s help) that the two 19th century technologies of the railroad and the telegraph were as socially and culturally transformative as the 20th century technologies of the internet and social media are today. And that the uneasiness about these changes was as great as the distress many feel about how our technologies are shaping society today. (In 1858, for example, the first transatlantic cable connected New York with London. The New York Times wondered if this might make the velocity of news “too fast for the truth”. Hmmm . . . )

Two of Will’s closing thoughts stand out: 1. “Technologies are giving velocity to stupidity, but not making people stupid”. 2. “Like railroads and the telegraph, today’s technologies have consequences about how and what we think. They do not relieve anyone of responsibility for either.”

As they relate to the political spectrum, I’ll (also regretfully) leave those thoughts without further comment. But let’s connect them to the educational arena.

We’ve talked before about the controversies surrounding technology and education. (Depending on how you define ‘technology’, this controversy is really not new.) Pick your topic – calculators, cell phones, internet, social media, etc, and there is so much debate about the ‘appropriate’ use of such items in the classroom.

This discussion can lead in two directions, it seems. I’ve likely said this before, but when it comes to the use of technology in the classroom, I’ve often thought we tend to ask the wrong question(s). The important question really ISN’T “should we use (fill-in-the-blank) in the classroom?”. The really pertinent questions are “what do we want our students to know (at any level)?” and “how can we effectively get them to learn it?”. If (fill-in-the-blank) doesn’t demonstrably help, why use it? But if it does help, why avoid it?

The other direction of the discussion is similar to one of Will’s points. Technology in the classroom does NOT make people stupid. This is ridiculous. That is wholly different, however, from the ‘stupid use of technology’ outside the classroom, which many think is happening at an alarming rate.

The final question, then, is this: “What is education’s role in teaching technology-related responsibility, and in preventing ‘stupid’ use of technology?” This is a much deeper question than it may appear. Should this be a role of education? What is the role of parents and society? Is this the same as teaching critical thinking? And if so, who gets to decide what’s ‘stupid’ and what’s ‘responsible’? And how do we ‘teach’ it?

The final question, then, is this: “What is education’s role in teaching technology-related responsibility, and in preventing ‘stupid’ use of technology?” This is a much deeper question than it may appear. Should this be a role of education? What is the role of parents and society? Is this the same as teaching critical thinking? And if so, who gets to decide what’s ‘stupid’ and what’s ‘responsible’? And how do we ‘teach’ it?

We adapted to railroads and the telegraph, and indeed, have gone beyond both. We will likely do the same today, but it will call for awareness and perspective. And education?

by Larry Campbell | May 1, 2021 | Education |

Once upon a time, so the story goes, there was a Wise Old Master who, despite his wisdom, seemed uncharacteristically glum one morning. When asked why, he responded: “It was a clear beautiful night last night, with the most spectacular full moon. So I decided to take the disciples outside for a wordless sermon. Standing among them in a field, I simply pointed at the moon.”

Once upon a time, so the story goes, there was a Wise Old Master who, despite his wisdom, seemed uncharacteristically glum one morning. When asked why, he responded: “It was a clear beautiful night last night, with the most spectacular full moon. So I decided to take the disciples outside for a wordless sermon. Standing among them in a field, I simply pointed at the moon.”

When asked why this dejected him, he replied “all the disciples knelt and worshipped the pointing finger.”

A couple of times recently, we’ve visited the idea of authentic student understanding, and I’d like to pull into that station again this week, for a couple of reasons. As I was thinking about this, I remembered the story above, and perhaps I’m stretching the analogy, but it seems like we – both in education and in as a public – might sometimes get ourselves in the position of the Wise Master’s disciples.

In our early March visit, I had been discussing my experiences with the concept of division in fourth grade. (https://larryncampbell.com/index.php/2021/04/26/short-division-student-understanding/). I mentioned that I was a whiz at ‘naked division problems’ themselves, while simultaneously spending time wondering why an answer like 5 R 3 (five, remainder 3) couldn’t just be ‘shortcut-ed’ to an answer of 8 by adding the 5 & 3.

I got an interesting response from Bob Egbert, frequent reader and former colleague in the MSU sciences: “As a student, back in the old days, I think I was able to perform without actually learning the material, especially in math. I could figure out what sort of problems would likely be on an exam (three to five problems none too involved given the time allotted for the exam) and off I’d go. I think that it wasn’t until some time later that I would say that I actually learned and really understood the material.”

Bob’s comment stuck with me, not only because of its relevance and its broad implications, but also because of his last sentence, which got me thinking.

I suspect we all have similar stories. These stories may come from any discipline, of course, but I think they tend to occur more often in my own field of mathematics (and arithmetic) because understanding of mathematics and what it is/isn’t often gets sidetracked with a metaphorical focus on pointing fingers.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/Division-Facts-3-56a602b45f9b58b7d0df7624.jpg) Consider the Wise Master and his disciples. Note that his pointing finger was in fact an important tool used to help acknowledge the goal: the beauty of the moon. But the tool was not the goal, and the disciples stopped short.

Consider the Wise Master and his disciples. Note that his pointing finger was in fact an important tool used to help acknowledge the goal: the beauty of the moon. But the tool was not the goal, and the disciples stopped short.

Likewise, just for one limited example, skill tests in mathematics (standardized or otherwise) can be an important tool – among many others – in helping assess student understanding. But they are not the final goal, and we shouldn’t stop too soon, thinking that they are. It’s a common hurdle in the difficult pilgrimage toward assessing authentic understanding.

Bob’s last sentence above highlights another factor to consider. How often do we all note that the real learning/understanding of a concept often comes slowly and in fragments? Don’t we all have stories of ‘learning’ something in school, but not ‘understanding’ it until later?

I’m wondering if that isn’t part of the natural process. If so, it creates an even more delicate balance in both teaching and assessing. How do we determine how a student is progressing and still allow time for that ‘maturation’ process of fully understanding? How, when, and how often do we assess?

It’s just another indicator of how complex the education process is and how well our schools manage to consistently achieve it.

by Larry Campbell | Apr 16, 2021 | Education |

If there’s anything to the idea of reincarnation, then I’m going to go way out on a limb and suggest that Missouri Treasurer Scott Fitzpatrick might have once been the PR point man for the Greeks in their battle with Troy. I can imagine the piece he would have written about that large horse sitting outside Troy, and how marvelous it would be if it rested inside the city instead.

Perhaps you read Mr. Fitzpatrick’s opinion piece that appeared in the News-Leader this past Saturday, April 10. (Educational Reform Should Have Bipartisan Support). Who can argue with his title? Indeed, there are certainly some statements he makes that I can wholeheartedly endorse, but like the Trojan Horse, I’m a little worried about what he seems to be hiding inside this inviting exterior. He seems to raise more questions than he answers. Let’s take a closer look.

Mr. Fitzpatrick’s goal – we finally learn – is to speak in favor of SB 55 and HB 349 in the legislature. He is ‘disappointed to see (legislative) opposition’ to these bills. This would presumably include members of his own party, since his party controls that same legislature. That might raise our first red flag.

Both these bills would create a voucher program which Mr. Fitzpatrick claims gives parents ‘more control over their children’s education’. True or not, what is unmentioned is that these are also bills which unquestionably provide public funding for private school choices, something that has historically not been favored by Missouri voters – or legislators.

I have stated before, and will honestly state again: I remain undecided, in principle, on the merits of charter schools. I have written columns listing pros and cons of charter schools (and home schooling, and other related ventures), and will openly re-state that under the best of circumstances, these programs can do things that public schools cannot. But past nationwide performances of charter schools, in particular, have generally not justified whatever potential they may possess. Partly this is because legislatures seldom, if ever, provide for accountability measures for the funding these schools receive and the services they provide.

So, when someone pushes this hard, with such potentially misleading arguments, we should at least get suspicious.

I mentioned misleading arguments. Mr. Fitzpatrick mentions, as part of his justifications that a ‘new problem’ is that ‘some kids might not be able to attend their public school because it is closed’, as if an unprecedented pandemic which has previously kept kids home for safety reasons is somehow tipping the scales toward providing public funds for private school choices. Really? Does that not somehow sound contrived?

Another question: Why is Mr. Fitzpatrick writing this piece? He was a legislator in the past but is now State Treasurer. He is neither a legislator nor an educator. Why venture an opinion? One notes that these bills would create a “Missouri Empowerment Scholarship Board”, which is chaired by the Missouri Treasurer. Would this provision grant him and his office extra political influence in how these education funds are spent?

I don’t claim to be an expert on all provisions of these bills. But It should be noted that the MSTA, MNEA (statewide groups of educators), MSBA (school boards), and MASA (administrators) are all opposed to both bills. Is this not troublesome? Was education-related input ever sought? These are two among several other questions needing asking here.

Mr. Fitzpatrick’s piece itself seems highly misleading (even ironically partisan?), and possibly self-serving. On that basis of his piece alone, we should be worried about a possible Trojan Horse in our midst.

by Larry Campbell | Mar 19, 2021 | Education |

I had the good fortune recently to learn of a great program that, among other things, connects older adults with younger students who have educational and other needs. It’s been in existence for a while, so maybe it’s only been me that wasn’t as aware of it as I should have been.

Sometimes I get caught up in encouraging support for – and ways to help in- public school programs themselves, and I almost forget that there are magnificent outside-the-school-walls community education programs that synergistically help promote educational growth and services as well. So let me plug a couple of those in the Springfield (MO) area today.

These two programs here are very similar in that they work with schools, parents, volunteers, businesses, and the community to partner in and encourage educational endeavors. They are quite different in the students and areas they serve and the opportunities they provide to get involved and help make a difference.

RSVP: Retired & Senior Volunteer Program

Sponsored by the Council of Churches of the Ozarks, this program engages adults 55 and older in meaningful community volunteer work that creates a sense of belonging for each volunteer. Among the available options are the Reading Buddies and the Pre-K Pals, which work as partners in local schools (Greene, Christian, and Webster counties).

The Reading Buddy Program utilizes volunteers to serve Kindergarten through 3rd grade students. Volunteers tutor children to read at grade-level. These mentors are matched with a student and spend at least 30 minutes with that student each week, reading books, doing activities, and mentoring. But they are also building rapport and a relationship that is meaningful for both the student and the volunteer. The student/volunteer pairing often creates close bonds for both.

The Reading Buddy Program utilizes volunteers to serve Kindergarten through 3rd grade students. Volunteers tutor children to read at grade-level. These mentors are matched with a student and spend at least 30 minutes with that student each week, reading books, doing activities, and mentoring. But they are also building rapport and a relationship that is meaningful for both the student and the volunteer. The student/volunteer pairing often creates close bonds for both.

(I also heard a rumor that there might be a new Math Buddy program in the works, though that is not official. Wouldn’t that be fun?)

During a school year, Pre-K Pals spend a couple hours a week meeting with two or three Pre-K students at a time to teach and practice social and emotional skills through reading-related activities. These skills (cooperation, self-control, engagement in learning, etc) are vital for kindergarten readiness.

Volunteers do not need to have experience in education to volunteer with RSVP. RSVP provides in-depth training for all volunteers during the summer before they are assigned to a school, with other training options during the year.

These programs are beginning to gear up again for the 21-22 school year (assuming no pandemic interference), and RSVP is seeking to rebuild their volunteer base. If you have questions, you can visit the RSVP website (http://ccozarks.org/rsvp/) or call Ronda Shehorn at 831-9696, option 1.

In addition, it turns out you can also see more about RSVP and others in the News-Leader’s recent Sunday (3/14, page 1C) feature on Literacy Programs.

So many incredibly rich and exciting opportunities in education and interpersonal relationships at work here!! Go adopt a(nother) grandchild!

O-STEAM: The Ozarks SySTEAMic Initiative

Working with students of all K-12 grade levels, this highly active program promotes Science, Technology, Engineering, the Arts, and Mathematics throughout the entire Ozarks Region. Visit their website at www.osteam.org to get a glimpse of the prodigious variety of activities and opportunities for students. These folks do really good work in the important STEM/STEAM fields of education.

One unique opportunity to help here exists in the area of business (and individual) sponsorships. Here’s a chance for your business to donate to a really good educational cause and get recognized as well. Personal donations are also welcome. And their website has a couple of other nice giving options as well.

by Larry Campbell | Mar 4, 2021 | Education |

Return with me briefly to my fourth grade school year (and bring your own dinosaur jokes with you). We’re headed to Mrs. Dice’s classroom at the end of the hall, where there’s a sharp right turn (both physical and metaphorical) into the 5th and 6th grade classrooms down that wing.

As we sneak into the back of the classroom, we observe that we were venturing into this new area called ‘short division’. (Did you encounter it?) Exciting new stuff! If we could learn these shortcuts, we would no longer have to multiply by the divisor, subtract the result from the original number, and repeat the process with the new number. (Yawn)

As we sneak into the back of the classroom, we observe that we were venturing into this new area called ‘short division’. (Did you encounter it?) Exciting new stuff! If we could learn these shortcuts, we would no longer have to multiply by the divisor, subtract the result from the original number, and repeat the process with the new number. (Yawn)

I now have to tell you that I was a whiz at arithmetic procedures that year. It you needed a times-tables or long-division answer, I was your man (or boy, I guess). But this is not to brag, as you’ll see.

I soon got good at this new procedure too. If I encountered a problem like 7 ‘goezinto’ 38, I could get the answer as 5, with a remainder of 3, using the shortcut procedures we were taught. We wrote this answer as 5 R 3.

Now here’s the problem. I could get that fine. But there was a period of two weeks or so that for the life of me, I didn’t understand why we needed two numbers in the answer! I mean, we have 5 R 3. Why isn’t the answer just 8? It was very puzzling to me. (And I didn’t have the courage to just ask.)

In summary, I could do short division problems lickety-split and get usually-perfect scores. But I didn’t ‘get’ that 38 could be split into 5 full groups of 7, with 3 left over that won’t fit into equal groups.

So, here’s the question: Given that limited scenario, would we say that I understood the concept of division? The quizzes (and perhaps the standardized tests) would say that I did. All correct answers, after all. But I’m pretty sure I know the dark secret that I really didn’t understand the concept during that time.

You may have deduced that I’m still pondering one of our topics from last time, namely the idea of student understanding, what it really means, and education’s surprisingly difficult task of evaluating when it is achieved – individually or as a group.

The example is from the field of arithmetic, and that’s probably because that’s buried in my ‘academic area’. Perhaps that’s why I remember my frustration so well? But we don’t have to limit our discussion to that subject.

After the events of the past two months (some would say the past 4 months – or even years), there’s been a lot of talk that we need to beef up the content in our school classes in history and civics, etc. But let’s think about that. I remember learning a lot of dates in history classes, studying a lot of maps, and learning a lot of facts (good and useful ones, I might add! And I remember many of them). But, did we really learn to understand the lessons of history or civics? Have we only recently come to learn and appreciate (the hard way) how valuable history is in our present times and how incredibly tough it is to be a good citizen, understand the Constitution, and to protect a democracy?

After the events of the past two months (some would say the past 4 months – or even years), there’s been a lot of talk that we need to beef up the content in our school classes in history and civics, etc. But let’s think about that. I remember learning a lot of dates in history classes, studying a lot of maps, and learning a lot of facts (good and useful ones, I might add! And I remember many of them). But, did we really learn to understand the lessons of history or civics? Have we only recently come to learn and appreciate (the hard way) how valuable history is in our present times and how incredibly tough it is to be a good citizen, understand the Constitution, and to protect a democracy?

So, we return to the beginning. We toss around the term student understanding as if we knew what we mean and automatically knew how to evaluate it. But do we? And will skills tests enlighten us?

by Larry Campbell | Feb 17, 2021 | Education |

Two topics have been pulling at me recently. Here’s a quick look at both:

Back to School. And Teachers. Again.

Back to School. And Teachers. Again.

Back-to-school talk is growing, and it seems almost everyone is on board. Parents, for the most part, are anxious (and of course, one empathizes with many of the reasons). Students themselves seem excited – also easy to understand. School administrations seem to want it, though perhaps that’s not universal? Politicians, now on both sides of the aisle, are pushing to get in-person classes restored. At least the current administration’s plan also includes considerable funding for both schools and states to make this easier and safer.

Seemingly unstoppable inertia and better safety planning have caused me to retreat somewhat from my earlier health concerns. But you can probably guess what still worries me. Reread the previous paragraph. It may become readily apparent that an all-important constituency in the equation is not mentioned. The teachers, of course. A strong case can be made that teachers are not only heroes in every manifestation of the pandemic responses, but they’re also the ones who have been under-appreciated, under-valued, and constantly getting short-changed, not only in terms of working conditions, but also in terms of input. Even if this movement were favored by everyone, it couldn’t happen for anyone without the teachers.

If the momentum is building, then shouldn’t states (and the CDC!) be more proactive in quickly moving teachers up the suggested priority lists for receiving vaccine shots? I’m fully aware that moving one group up in priority can affect other groups, including mine. But talk about ‘essential workers’!!

Student Understanding – An Enigma?

Student Understanding – An Enigma?

So easy to understand and agree on, at least in general principle. Yet there may be no harder concept to evaluate in all of education.

These thoughts re-surface now, out of an e-mail exchange after my last column. The column contained two quote/excerpts that I wanted to re-share. One of them contained an inspiring vision for mathematics education, and – almost as an afterthought – I had dropped in the opinion that progress was indeed being made in exactly those directions.

A reader asked (politely, yet dubiously?) what empirical evidence I had to support that opinion. He commented that as a parent and grandparent (with former graduate math classes in his background), “I can’t say that I’ve seen any improvement in math understanding over time, and in fact it appears worse!”

As to his question, it was a fair one, and I did not necessarily want to dodge it. And further, I do not doubt his perception that he sees no evidence of improvement in math understanding, any more than I doubt my own perception that I do see such evidence.

So, therein lies the (first) fly in the ointment. What if both of our perceptions are ‘correct’, based on our own understanding of the tricky term ‘math understanding’?! (And that, in turn, is likely based on what each of us believes ‘math’ itself is – and isn’t – a whole other topic!)

I said most of this in my reply, and, in order to begin to pin down our perceptions, I asked his question back to him. I generally asked him, in his experience, what kind of evidence he ‘didn’t see’ to support the lack of ‘math understanding’. This is, what evidence would he want to see?

I haven’t heard back yet – perhaps I’ve lost him. But the age-old educational question remains: Exactly what is ‘student understanding’ (in general, not just in math), and far more importantly, how do we determine when it exists for a student in a subject? Do ‘achievement tests’ do that? Watch for more.

The column refers heavily/often to a book called “Lincoln on the Verge: Thirteen Days to Washington”, by Ted Widmer, a historian at City University of New York. The book is apparently a detailed record of president-elect Lincoln’s 1861 journey by train from Springfield, Ill to Washington, DC.

The column refers heavily/often to a book called “Lincoln on the Verge: Thirteen Days to Washington”, by Ted Widmer, a historian at City University of New York. The book is apparently a detailed record of president-elect Lincoln’s 1861 journey by train from Springfield, Ill to Washington, DC.  I’m regretfully omitting fascinating background here, but in a nutshell, Will concludes (with Widmer’s help) that the two 19th century technologies of the railroad and the telegraph were as socially and culturally transformative as the 20th century technologies of the internet and social media are today. And that the uneasiness about these changes was as great as the distress many feel about how our technologies are shaping society today. (In 1858, for example, the first transatlantic cable connected New York with London. The New York Times wondered if this might make the velocity of news “too fast for the truth”. Hmmm . . . )

I’m regretfully omitting fascinating background here, but in a nutshell, Will concludes (with Widmer’s help) that the two 19th century technologies of the railroad and the telegraph were as socially and culturally transformative as the 20th century technologies of the internet and social media are today. And that the uneasiness about these changes was as great as the distress many feel about how our technologies are shaping society today. (In 1858, for example, the first transatlantic cable connected New York with London. The New York Times wondered if this might make the velocity of news “too fast for the truth”. Hmmm . . . ) The final question, then, is this: “What is education’s role in teaching technology-related responsibility, and in preventing ‘stupid’ use of technology?” This is a much deeper question than it may appear. Should this be a role of education? What is the role of parents and society? Is this the same as teaching critical thinking? And if so, who gets to decide what’s ‘stupid’ and what’s ‘responsible’? And how do we ‘teach’ it?

The final question, then, is this: “What is education’s role in teaching technology-related responsibility, and in preventing ‘stupid’ use of technology?” This is a much deeper question than it may appear. Should this be a role of education? What is the role of parents and society? Is this the same as teaching critical thinking? And if so, who gets to decide what’s ‘stupid’ and what’s ‘responsible’? And how do we ‘teach’ it?

Once upon a time, so the story goes, there was a Wise Old Master who, despite his wisdom, seemed uncharacteristically glum one morning. When asked why, he responded: “It was a clear beautiful night last night, with the most spectacular full moon. So I decided to take the disciples outside for a wordless sermon. Standing among them in a field, I simply pointed at the moon.”

Once upon a time, so the story goes, there was a Wise Old Master who, despite his wisdom, seemed uncharacteristically glum one morning. When asked why, he responded: “It was a clear beautiful night last night, with the most spectacular full moon. So I decided to take the disciples outside for a wordless sermon. Standing among them in a field, I simply pointed at the moon.”:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/Division-Facts-3-56a602b45f9b58b7d0df7624.jpg) Consider the Wise Master and his disciples. Note that his pointing finger was in fact an important tool used to help acknowledge the goal: the beauty of the moon. But the tool was not the goal, and the disciples stopped short.

Consider the Wise Master and his disciples. Note that his pointing finger was in fact an important tool used to help acknowledge the goal: the beauty of the moon. But the tool was not the goal, and the disciples stopped short. The Reading Buddy Program utilizes volunteers to serve Kindergarten through 3rd grade students. Volunteers tutor children to read at grade-level. These mentors are matched with a student and spend at least 30 minutes with that student each week, reading books, doing activities, and mentoring. But they are also building rapport and a relationship that is meaningful for both the student and the volunteer. The student/volunteer pairing often creates close bonds for both.

The Reading Buddy Program utilizes volunteers to serve Kindergarten through 3rd grade students. Volunteers tutor children to read at grade-level. These mentors are matched with a student and spend at least 30 minutes with that student each week, reading books, doing activities, and mentoring. But they are also building rapport and a relationship that is meaningful for both the student and the volunteer. The student/volunteer pairing often creates close bonds for both.

As we sneak into the back of the classroom, we observe that we were venturing into this new area called ‘short division’. (Did you encounter it?) Exciting new stuff! If we could learn these shortcuts, we would no longer have to multiply by the divisor, subtract the result from the original number, and repeat the process with the new number. (Yawn)

As we sneak into the back of the classroom, we observe that we were venturing into this new area called ‘short division’. (Did you encounter it?) Exciting new stuff! If we could learn these shortcuts, we would no longer have to multiply by the divisor, subtract the result from the original number, and repeat the process with the new number. (Yawn)  After the events of the past two months (some would say the past 4 months – or even years), there’s been a lot of talk that we need to beef up the content in our school classes in history and civics, etc. But let’s think about that. I remember learning a lot of dates in history classes, studying a lot of maps, and learning a lot of facts (good and useful ones, I might add! And I remember many of them). But, did we really learn to understand the lessons of history or civics? Have we only recently come to learn and appreciate (the hard way) how valuable history is in our present times and how incredibly tough it is to be a good citizen, understand the Constitution, and to protect a democracy?

After the events of the past two months (some would say the past 4 months – or even years), there’s been a lot of talk that we need to beef up the content in our school classes in history and civics, etc. But let’s think about that. I remember learning a lot of dates in history classes, studying a lot of maps, and learning a lot of facts (good and useful ones, I might add! And I remember many of them). But, did we really learn to understand the lessons of history or civics? Have we only recently come to learn and appreciate (the hard way) how valuable history is in our present times and how incredibly tough it is to be a good citizen, understand the Constitution, and to protect a democracy? Back to School. And Teachers. Again.

Back to School. And Teachers. Again. Student Understanding – An Enigma?

Student Understanding – An Enigma?