by Larry Campbell | Oct 14, 2020 | Education |

“Suppose the COVID19 test is 97% accurate, and you’re in a room where everyone has just tested Negative. With that 97% confidence-level percentage, how many people would it take in the room to have a 50-50 chance that someone’s test is inaccurate?”

“Suppose the COVID19 test is 97% accurate, and you’re in a room where everyone has just tested Negative. With that 97% confidence-level percentage, how many people would it take in the room to have a 50-50 chance that someone’s test is inaccurate?”

What an interesting question! It came from a participant in a pre-pandemic Math-is-Fun-type class for senior adults at MU in Columbia. I’ve edited it slightly to begin the process of making it more precise.

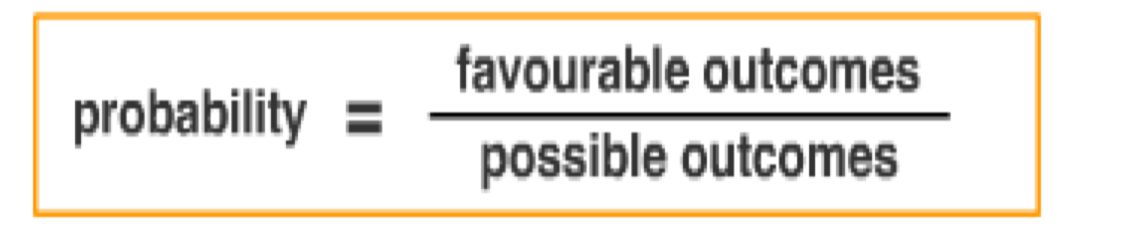

I was instantly intrigued by the question, partly due to its topical nature, and partly because it is a question that can conceivably be answered in a relatively straightforward manner, using techniques from mathematical probability. But I was further intrigued by the fact that like any real-world problem, the situation presents questions and conditions that need to be clarified before mathematics can help. (If the conditions get changed or redefined, so can the mathematical answer.)

Disclaimers: I am not a medical expert. I’m not sure if the 97% figure is technically ‘correct’, and I haven’t even devoted much effort to checking. (It’s not terribly relevant to our broader point, and I suppose various tests have various associated levels of accuracy.) Further, I’m not sure (and haven’t been able to pin down) what it means for this test to be ‘inaccurate’, that is to say a test yielding a ‘false negative’ result. This is important here, because I don’t think (recall disclaimer!) that a ‘false negative’ result is the same as a ‘positive’ result. It could simply mean ‘test fails’ for some reason.

And of course, we should note in passing that a ’50-50 chance’ is just exactly that. It certainly does not guarantee that someone in the room has a false-negative test.

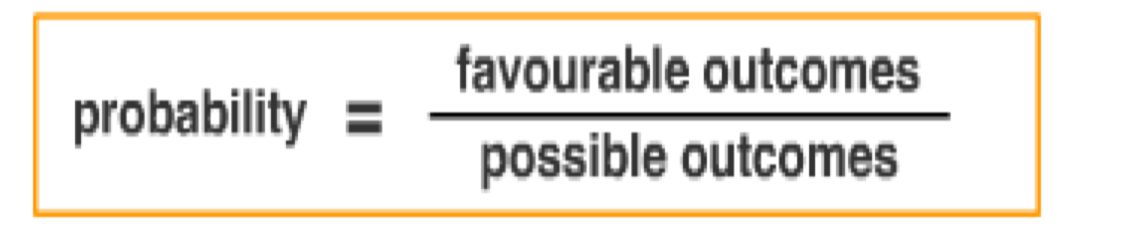

Nonetheless, no matter how the questions above are answered, the mathematics is relatively straightforward. Not necessarily middle-school-easy, of course, but not difficult in a basic probability class or unit. For the reader’s sake, I won’t go through the mathematics here. But neither do I expect you to believe me blindly. I am happy to elaborate with anyone interested.

Nonetheless, no matter how the questions above are answered, the mathematics is relatively straightforward. Not necessarily middle-school-easy, of course, but not difficult in a basic probability class or unit. For the reader’s sake, I won’t go through the mathematics here. But neither do I expect you to believe me blindly. I am happy to elaborate with anyone interested.

But I can give the results for the problem as stated in the opening paragraph. To be as precise as possible, if the test is 97% accurate, and if everyone in the room has tested negative, then it only takes 23 people in the room to have a better-than-even chance that at least one person’s test is a ‘false negative.’ With 30 people, the probability goes up to 60%.

That result is most interesting to me. It provides a new and perhaps more relatable perspective. It only takes 23 people in a room of negative tests to make it semi-likely (not certain!) that a test is inaccurate. Even if ‘false negative’ does not mean ‘positive’, it’s somewhat worrisome. If ‘false negative’ actually meant (or means) positive, then it’s getting serious.

(Interesting: if the test is 98% accurate, then it takes 35 people in the room, instead of only 23. At 99%, it jumps to 69 people.)

As always, what is the broader educational perspective here? I believe it is this. Maybe it’s a stretch for this particular problem, but Isn’t this roughly the general kind of ‘real world’ question/situation that we want our future graduates to be able to intelligently articulate, tackle, and define conditions for, regardless of their interest in mathematics? Once the question and conditions are made precise, a math type can be consulted if needed.

Regardless of their fields of interest, we say we want our future citizens to become better critical thinkers. These are the general kinds of situations that demonstrate that need.

by Larry Campbell | Sep 28, 2020 | Education |

“Everybody is a genius. But if you judge a fish by its ability to climb a tree, it will live its whole live believing that it is stupid.”

This quote is frequently attributed to Einstein, though there is no evidence he ever said it. It appears to have emerged from an old allegorical tale. Nonetheless, for me, it is slightly reminiscent (not in a physics way!) of Einstein’s ‘thought experiments’ and I think pondering the metaphor can be just as thought-provoking and enlightening. The quote effectively highlights one of the many areas that makes public education so incredibly complex.

Our schools interact with millions of children every year. We meet them as adorable youngsters in a Kindergarten equivalent, and over a decade later, we graduate them from high school as young adults moving into the next phases of their lives. At issue then, is this: What happens to them, and for them, during those formative years while they are in our classrooms?

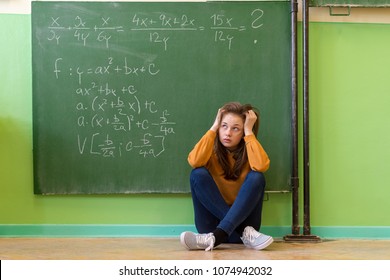

For educators – for all of us, really – this translates into at least two other questions. How do we most effectively educate all students when every student is different, when many students learn in different ways and styles, and when some of those students have special gifts and/or special needs? Even trickier, how do we provide every student the opportunity to discover what they do best, where their interests (and therefore gifts?) lie, and what unique guidance they will need?

These are formidable goals to uniformly achieve for all our students. The tasks are made more difficult by the nature and limitations of ‘the system’. Over the decades, out of unfortunate near-necessity, we have typically used a one-size-fits-all approach. This has worked relatively well for many, maybe most, of our students, and it has allowed the system to do many things more efficiently for the majority. But it has also worked to the detriment of individual students who don’t navigate well within the system.

In the spirit and context of the opening quote, then, we can re-ask those questions: How do we keep from evaluating the metaphorical fish on its ability to climb trees? And, how do we locate the fish and help them discover they were never meant to climb trees, but have another destiny instead?

Consider one of many examples: Currently sitting in our elementary classes (or learning online!) we have a perhaps-sizeable contingent of budding artists, poets, musicians, mystics, and the like. In two or three decades, they could be reminding society of the value of making a life while we also make a living. How do we help these students find their voice, awaken their gifts? And how do we keep from labeling them as inattentive (or ‘slow’ or ‘stupid’) when they are squirming in, say, a math or social studies class? (As a practical matter, this gets tougher still when many schools are trimming, even eliminating art, music, and more from their curricula!)

And in passing, we note that history is full of geniuses who did not do well in school. Folks like Michelangelo, Beethoven, Edison – even Einstein – were essentially ‘fish out of water’ in their school years. Some of them were labeled dull, or even incorrigible. Would they have achieved their genius today?

We know there are no good ‘right answers’ to these questions, but educators continue to ask them, as we all must. Perhaps a deeper dive into these issues will follow. In the meantime, the perspective for today is the ongoing reminder (sound familiar?) that that education is an incredibly complex endeavor and the simple act of constantly remembering that can help work miracles.

by Larry Campbell | Sep 19, 2020 | Education |

Within roughly 24 hours in this past week, I ran into two cartoons that dealt with topics we have kicked around before, one of them as recently as the last column. They both dealt with common misconceptions and/or favorite complaints about mathematics. And they were both just varied enough that I thought taking another look at the topics might be beneficial rather than redundant.

Plus everyone likes cartoons, right? Especially if they reinforce your view of math? Here are the cartoons and such.

1] The Baby Blues comic strip one week ago today (9/10/20) showed the father passing the daughter sitting on the couch. He asks what she is doing and she replies “Just some online learning.” When the dad asks what kind, she says “Math.” He looks over at her laptop and says “Zoe, that’s a shoe sale.” She answers with a grin, “Sizes, prices, discounts – it’s all numbers!”

2] A friend posted this cartoon on Facebook. The scene: A young couple having a deep discussion. “Share a book that made you cry,” she says. He replies “Algebra I.”

Another friend added this comment: “When I was in seventh grade, all we did in math was add, subtract, multiply and divide . . . and it would put me to sleep. I never got over it.” Two or three other friends piled on with similar comments, with the word ‘algebra’ mentioned rather as a curse word.

So, we’re looking at the numbers-and-math confusion and the never-good-at-math themes again. Different topics, but definitely related. Great fun. Comments below refer to corresponding numbers from above.

1] Numbers and mathematics are indeed (usually) inextricably linked. But, like words and writing, or scales and music, they are not the same thing. (When someone says ‘do the math’, they usually mean ‘do the arithmetic’ and that subtlety can cause real perception problems.) Just dealing with numbers, or even doing arithmetic, is not really the same thing as doing math (solving problems) in general.

This is not to say that numbers themselves can’t be fun, of course!! As we’ve mentioned in the past, a person can love both numbers and math, or they can love one and not the other. And, of course – I feel you saying it – they can love neither, which really isn’t as universal as might be thought.

2] As discussed just last time, some of this dislike of math is our (we teachers’) fault. Doing arithmetic with long columns of numbers is no more doing mathematics than playing lots of scales is making music. And still doing this in 7th grade – even way back when – is just this side of a crime. And it tends to drive students away.

Naturally, practice in ‘skills’ is needed in both math and music, especially music. Pure arithmetic practice (like times tables!) is not needed as much these days, thanks to the advent of technology. (This is not evil – it actually allows us more time to get to the problem solving!).

Unfortunately, in elementary school math education, we haven’t made that number/math distinction – or shared that final beauty – nearly explicitly enough or nearly often enough for our students. And, in the past, we’ve been too often boring in our here’s-what- to-do presentations. Because of that, we have lost prospective enthusiasts, and picked up budding haters.

Luckily, things are better these days than they used to be. Even today though, part of the problem with developing young thinkers, problem solvers, and yes – math lovers – is helping students understand what we’re doing and why, and then finding a way to transition from numbers/skills to math/thinking in a way that is not boring and that can maintain their interest.

by Larry Campbell | Sep 6, 2020 | Education |

Drawn Into the Fun

It all started with one of those “if you get this, you are a critical thinker” brain teasers posted on Facebook. I should have moved on, but I love brain teasers and the ‘critical thinker’ part beckoned.

It all started with one of those “if you get this, you are a critical thinker” brain teasers posted on Facebook. I should have moved on, but I love brain teasers and the ‘critical thinker’ part beckoned.

It eventually more/less ended with one of my friends jokingly telling me that I ‘would debate the wetness of water!’ Like I said, I should have known better.

I will share the brain teaser, but slightly altered. This will likely hurt some of the context, and ruin part of the fun. But I suspect you’ll deduce my reasons. Here is the riddle:

“You are in a paintball tournament. Players who are ‘paint-balled’ are eliminated and must freeze where they are. You enter a room. There are 34 people. You manage to paintball 30. How many people are in the room?”

As a math teacher who used to preach the importance of conditions in a problem, the problem grabbed me as a great example. I was noticing how there could be several (correct) answers, depending on the conditions you adopted. And how that would make a great ‘word problem’ discussion.

Posted solutions were ranging all the way from 0 to 35, some with interesting (and to me, valid) explanations. Questions were posed, such as ‘are you one of the 34?’, ‘do people leave after they’re paintballed?’ and others.

This was exciting to me, as I would have loved for students to be asking those questions without fear. I tried to briefly share some of that excitement/perspective. I quickly realized that this classroom-related excitement was not shared, and it led to the accusation that I would debate the wetness of water. Leave it to a math teacher to kill the fun?

The One Right Answer

It turns out that ‘The Right Answer’ was “One person. The room you entered had a window opening through which you paintballed your victims in another room, so you were alone in the room.”

Part of me appreciated the fun and ingenuity of that ‘answer’. (I’d even finally decided that’s what was wanted.) It was great for think-outside-the-box. But, I also thought other folks’ options were OK, too, and would have encouraged those options in a class discussion. But the above was The One Right Answer, and all else was Wrong.

All this was no big deal. It was all in fun, and these days ‘fun’ on Facebook is refreshing!

The Aha! Reminder

But here’s the point for today: How’d you feel when you read ‘The Answer’? For me, I was suddenly struck with this overwhelming feeling: “Ah, yes. This is partly why many kids begin to hate math!! They’re always expecting a ‘trick’.” They become convinced that math consists of rules/tricks that come out of the blue, that they can never possibly learn all this no-sense junk, and what’s the use anyway?

The irony? Younger students, say pre-k into early grades, typically love numbers, games with numbers, etc. But as we try to move into learning to use numbers to help solve problems (arithmetic), and byond, it seems they begin to lose interest.

Could that be our fault? It’s likely. The math education community has recognized this forever, and much impressive progress has been made here. And, to be clear, I continue to love good Brain Teasers, both in and out of the classroom. They can keep things fun and be instructive at the same time.

But, as we work to teach students to solve problems (math and otherwise), we continue to move away from “Here’s what you do. Do it” to “There’s more than The One Right Way, and often more than One Right Answer. Here are some tools to help.”

by Larry Campbell | Aug 19, 2020 | Education |

A College Memory

Thankfully, this is no longer politically correct, but way back in my college days, college fraternities had Hell Weeks. In my case, this was a small, conservative, Baptist college, (and this was well before some of the horror stories of the past few years), so it was more like “Heck Week”, but there was still lots of tomfoolery to be endured. (Try reciting the Greek alphabet 3 times while holding a burning match.)

During my own week, one of the upper-class members with a saner perspective pulled me aside in mid-week, and quietly suggested, “Look – if you’re given two contradictory commands, just do the one that is easier/better for you.” Hold that thought.

Recent Happenings

Educationally, things have changed quickly and drastically. I believe the time has come to face the fact that schools are in a damned-if-they-do-or-don’t situation with respect to reopening, staying open, or re-closing. National experiences of recent weeks have begun to strongly suggest that we are simply not quite ready for person-to-person learning again, at least in public schools.

Part of me wonders ‘how can we even think that?!’ But the rest of me wonders, equally as loudly, “How can we NOT think that?” Contradictory messages. Which is why I remember the above advice from my college days. Isn’t it beginning to seem that the ‘better for all’ choice is safety for our children and teachers, while dealing with the unique fallout as best we can?

Please. This is not to minimize this undesirable fallout in any way. Whole new paradigms will emerge as parents try to deal with children at home and the need to be at workplace. It will continue to be difficult, if not impossible, for children in poverty without laptops to have access to online learning. And so on. It’s all a horrible nightmare. But it’s now the smaller of the two nightmares, and it’s one where we can all help.

The Big Question(s)

So let’s face the big question head on. What educational options exist for schools, parents, and our society if we are all forced to adjust to the un-dreamed of circumstances of no physical school?

First let’s note that not being in school isn’t necessarily the same as not learning. Even with the apparent flaws, let’s at least start with various and obvious ways to increase learning at home, whether that learning comes from schools, parents, outside sources, or other creative ventures.

New Paradigms?

Second, we have an opportunity (albeit unwanted) to get creative and think outside the box. What kind of never-before-needed ideas might be out there? Naturally, these aren’t immediately obvious, so I certainly can’t predict them. But the ideas would bubble up, partly because they’d have to.

Perhaps stuck-at-home substitute grandparents e-mailing with students on topics of interest? Small groups of (adult-led?) students attending Zoom meetings on topics of interest? Previously untapped outside educational resources/activities, both with schools and elsewhere? Inventive extra-curricular activities that are ripe with potential for learning? These are clearly spur-of-the-moment brainstorms, but as with many cases of lemonade from lemons, others would develop, multiply, and be fruitful.

If there is ANY silver lining to this pending scenario, it is the one above that almost excites me. We’re probably aware of literally dozens of marvelous inventions that emerged from previous plagues, wars, economy collapses, and other past widespread calamities. (A Google search yields dozens!)

So what kind of ideas or new educational paradigms might emerge from the circumstances forced on us by this world-wide pandemic? Can we step out a level and at least hope there’s a chance that future generations might look back and say, “(that educational paradigm/invention) we now take for granted might never have occurred if there if it hadn’t been for the Covid19 pandemic of 2020”?

by Larry Campbell | Aug 5, 2020 | Education |

It was a microcosm of the difficult world we now navigate daily, and apparently it was extremely difficult, even sad, to watch. One knew it wouldn’t end well, period. How could it?

The recent Branson (MO) Council debate over the face-mask mandate was a perfect example of trying to balance the health of a community’s economy with the health of a community’s residents. Tales and pleas from agonized businesses were sad and touching. Facts and pleas from the healthcare community were sober, even frightening. How tragic that the pandemic dictates that these two valid concerns must face off in a way-too-literal case of ‘pick your poison’!

Why these thoughts in a column about education? Because the whole back-to-school debates are frighteningly similar. It’s hard to hear/read about one ‘side’ or the other without feeling compassion and sympathy. How can we balance the metaphorical health of a community’s schools with the literal health of a community’s residents, including children, teachers, administration, staff, parents, extended family, neighbors? How cruel that we should be faced with that ‘pick your poison’ choice! And how cruel that it’s not going to end well, either way.

Another parallel to the mask situation/choice: It was hard to see and hear of the too-frequent lack of understanding – even hostility – of either side for the other. It’s indicative of our current divided climate, but there was apparently little evidence of understanding of and respect for each side’s individual and common goals to seek win/wins for these unprecedented circumstances.

Can these unyielding stances be softened in the school re-opening debates, or is it already too late? Do these choices have to be either/or? Can both sides work together?

These times just aren’t normal. Each position has obvious valid concerns, or the dilemma wouldn’t be so massive. Can they be honored and addressed together, to minimize the lose/lose nature of the choices? Or, is that too old-fashioned to fit in today’s society?

I repeat that I don’t think there’s a universal right answer. Instead, I continue to strongly support allowing/encouraging EACH school district (working with constituents) to make these difficult decisions for themselves, regardless of the noise from Washington. And I would hope each community could somehow band together to support those decisions and work to give them better chances to succeed.

Three final thoughts, each of which could probably be a separate column:

- Surely I’m wrong, but it’s feeling like teacher health and work/load concerns are not always getting the full consideration they deserve. We ‘demand’ this and that from schools and tend to just assume teachers will always be there, even to do double duty with person/person and virtual learning. To me, this is dangerously like keeping a car constantly polished and waxed, but never adding gas or changing the oil. Teacher ‘health’ (physical and mental!) is also crucial. Stories of them writing wills and/or considering retirement are heartbreaking.

- As so often is the case, we don’t give schools a break. We ‘demand’ so much from them, yet we give them so little credit for their plans, their work, and their creativity as they try to do the impossible. Can we trust and work with them more, and blindly criticize less?

- Let’s face it: Some schools may not reopen. Or they may close again relatively soon. For an indefinite time. I say this so very carefully, but, in the long-range big picture, I believe this wouldn’t be the apocalyptic scenario that it might feel like in our short-range conditioned mindset. And, in the not-too-distant future, when the dust has cleared, and the pain has lessened, we may look back and see that scenario as the perfect lesser-of-two-evils situation.

Nonetheless, no matter how the questions above are answered, the mathematics is relatively straightforward. Not necessarily middle-school-easy, of course, but not difficult in a basic probability class or unit. For the reader’s sake, I won’t go through the mathematics here. But neither do I expect you to believe me blindly. I am happy to elaborate with anyone interested.

Nonetheless, no matter how the questions above are answered, the mathematics is relatively straightforward. Not necessarily middle-school-easy, of course, but not difficult in a basic probability class or unit. For the reader’s sake, I won’t go through the mathematics here. But neither do I expect you to believe me blindly. I am happy to elaborate with anyone interested.